Oregon Route 2

|

|||

| Oregon Route 2 | |||

| Wolf Creek Highway #47 (1932-1946) Timber Road (1939-1941) Gales Creek Road (1939-1941) Tualatin Valley Highway #29 (1940-1948) Nehalem Highway #102 (1941-1948) Sunset Highway #47 (1946-1951) |

|||

|

|||

| Route Information | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Maintained by Oregon State Highway Department | |||

| Length | ≈3.77 mi. | ||

| Existed | June 22, 1932 to October 21, 1951 | ||

| Junctions | |||

| West End | |||

| East End | |||

| Navigation | |||

|

|||

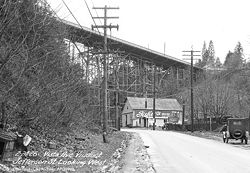

Oregon Route 2 was one of the original primary state routes when the system debuted on June 22, 1932. Originally assigned along a nebulous corridor of a "short route to the sea" from Portland, it was routed along the Wolf Creek (now Sunset) Highway #47. Because most of the chosen routing required new construction between Necanicum Junction and Sylvan, OR-2 likely wasn't first signed until 1939 when it was opened to traffic between Necanicum Junction and Sunset Camp, with a temporary routing to Forest Grove along county roads. After a westward extension to Cannon Beach Junction and delays in construction due to World War II, the full route of the Sunset Highway wasn't opened to Sylvan until 1948. US-26 was extended along the entirety of OR-2 in October 1951, eliminating the designation.

Contents

History

Prior to OR-2 Designation

While most of OR-2 was constructed along a new alignment, parts were designated along roads that existed prior to 1932.

Portland to Sylvan

In 1848, Portland tannery owner Daniel H. Lownsdale received permission to survey a road from Portland westward through the Tualatin Mountains (now known as the West Hills) along the Tanner Creek Canyon through what is now Sylvan, Beaverton and Hillsboro to Lafayette[1]. This road would open in 1849, providing a much-needed connection between the fertile Tualatin Valley farmlands and the growing city of Portland[2]. Unfortunately, the route soon became impassable due to mud. In response, Lownsdale petitioned the Oregon territorial government to construct a tolled wooden plank road, called the Great Plank Road, to replace it; his charter for the Portland & Valley Plank Road Company was approved in August 1851[1]. The first planks were laid at Portland's western plat line, close to the present day Portland South Park Blocks along SW Jefferson Street, on September 27 that same year[1].

The road's construction was mired in financial mismanagement in subsequent years[3] and the territorial government chartered a new company, Portland and Tualatin Plains Plank Road Company, in February 1856 to take over and complete the road[1]. Nevertheless, the road -- renamed Canyon Road by this point -- was completed to Beaverton by 1860, costing between $1 and $5 to use depending on the weight of the cargo[4]. However, wooden plank roads deteriorated rapidly in Oregon's cold wet climate, and by 1867 there were already calls to macadamize the increasingly impassable road[1]. Despite calls by The Oregonian in 1872 to supplant plank roads like Canyon Road with railroads[5], a new road appears to have been surveyed by late March of that year and constructed soon after[6]. In 1885, the Oregon House of the Legislative Assembly passed a bill providing $1,000 in funding to maintain Canyon Road over a two-year period[7][8].

In 1897, Canyon Road was mentioned as a bicycling route in the Oregon Division of the Legion of American Wheelmen's Road Book of Oregon[9]. It was paved to some degree by 1921.

At the March 21, 1921 meeting of the OSHC, Canyon Road between Beaverton and Portland was designated as part of the Tualatin Valley Highway #29[10]. The request was made by Lewis A. McArthur, the Secretary of the Oregon State Geographic Board at the time.[10]. While the state took over the entirety of Canyon Road between Beaverton and the county line, Multnomah County retained jurisdiction over their portion; this was due to a provision in the 1917 highway program wherein Multnomah County would fund the construction and maintenance of any state highway that passed through it[11]. The state wouldn't take over the Portland-Sylvan part of Canyon Road until January 16, 1931[12], readopting it on May 18, 1937[13].

Multnomah County reconstructed much of its section Canyon Road between 1926 and 1930[14]. Winding through the canyon west of Portland to Sylvan, The Oregonian called it "the finest piece of highway in the state" at the time[15]. The state paved and relocated its portion of Canyon Road from Beaverton to Sylvan in concert with Multnomah County[15].

Elsie to near Sunset Rest Area

This segment closely follows the path of the partially-built Salem-Astoria Military Road. Attempts by Oregon's provisional and territorial governments to build such a road between Salem and Astoria via the Tualatin Valley failed in 1843 and 1848 respectively[16]. Settlers eventually persuaded the US Congress to send the US Army Corps of Topographical Engineers to survey and construct the road[16]. In July 1855, the survey team, conducted by Lt. George Derby and his team of 10 men and 6 pack animals, began their general survey from Astoria towards Salem; a more detailed survey was performed on the return trip to Astoria the next month[16].

Behind schedule by 8 months, construction of the Salem-Astoria Military Road began in 1856[16]. Funding also became an issue, with costs exceeding the initial $30,000 allocated to the project and intermittent funding causing stoppages[16]. Furthermore, Lt. Derby was unable to find laborers who would build the road for $60 per month (or just over $2,000 in 2021 dollars) due to a gold discovery along the Colville River in present-day Washington state[17]. Nonetheless, almost 53 miles of the road opened by 1858; the Astoria side made it to the Nehalem River near Elsie, and the Salem side made it to Timber[17][16].

The outbreak of the Civil War eliminated funding for the military road, which was now the responsibility of the individual counties to complete[16]. These counties never did end up completing the road to its 16-foot width standard, though a pack trail connected the two ends[18]. While the road became an important mail route in later years, wagons weren't able to traverse the route until 1895, and it certainly couldn't handle the horseless carriages and cars that followed in subsequent decades[18].

Cannon Beach Junction to Necanicum Junction

By 1895, a road existed between what is now Cannon Beach Junction and the Necanicum River about 4 miles to the east, as part of a longer coastal road from Astoria to the Clatsop/Tillamook county line and beyond. This original road appears to diverge south of modern-day US-26 near the Black Bridge over the Necanicum River, and is now known as the Necanicum Mainline.

Sometime in the 1910s, the unimproved 1895 road was extended eastward across the Necanicum River to what is now Necanicum Junction, where it also turned south towards the county line. The entire coastal road from Astoria to the county line, including this segment, was designated as part of Coast Highway #3 on November 27, 1917 by the OSHC[19]. The name of the highway was changed to the Roosevelt Coast Military Highway by 1919[20]; it later was referred to as the Roosevelt Coast Highway, Roosevelt Highway and Coast Highway until it was officially changed by law to the Oregon Coast Highway on February 27, 1931[21]. Also, at some point between 1918 and 1920, its highway number changed from #3 to #9, the current number of the Oregon Coast Highway.

On November 11, 1926, this section of road, along with the rest of the Coast Highway in Oregon, was designated US-101 by the American Association of State Highway Officials[22].

A "Short Route to the Sea"

In the 1870s and 1880s, resorts and towns started springing up along the northern Oregon coast catering to vacationing Portlanders arriving in Astoria by ferry. To keep up with the influx, a railroad between Astoria and Seaside was opened in 1889[23]. The region was further connected by the opening of a rail line between Astoria and Portland in 1898[24] and the Lower Columbia River Highway between Seaside and Portland via Astoria in 1916[25]. While these developments were instrumental in bringing the travel time between Portland and Astoria down to about 5 hours, other Clatsop County coastal communities and Portland businessmen sought a faster, more direct connection between the two regions[26].

In the mid-1900s, highway enthusiast Samuel Reed proposed a plan for a short road between Portland and the Seaside/Cannon Beach region to the Portland Chamber of Commerce[27]. However, it wasn't until the 1920s that the public started clamoring for such a road, with numerous routes suggested and advocated for by residents along each route's path[15]. With support for the road growing even as the Great Depression hit, the OSHC initiated a study of the road in August 1930[28][29]. Though the routing and the western terminus was under investigation, it was widely expected that the eastern terminus would be in Sylvan at a junction with Canyon Road[15]. In addition to extensive ground reconnaissance, the OSHD utilized aerial photography for the first time to survey possible routes for the short road to the sea[29].

The survey results were originally expected in the summer of 1931, but were completed and presented to State Highway Engineer Roy A. Klein by mid-January, far ahead of schedule[29]. Six routings were surveyed, studied and ranked according to several factors, including construction cost[30]:

| Rank | Name | Routing | Est. Cost[30] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ridge Route | From Glenwood, it would have followed modern-day OR-6 to about Storey Burn Road, then would have traveled north and west around Larch Mountain towards Blue Lake, following Cook Creek and the Nehalem River to Mohler | $2,510,002 |

| 2 | Wilson River Route | From Glenwood, it would have largely followed modern-day OR-6 to Tillamook, save for slight deviations | $2,793,794 |

| 3 | Vernonia-Hamlet Route | From Vernonia, it likely would have roughly followed Keasey Road to Keasey, then traveled west to near modern-day OR-103 near Grand Rapids, then roughly followed OR-103 to Elsie, then crossed modern-day US-26 southwest to Hamlet, then followed Hamlet Road to Hamlet Junction near Necanicum | $3,177,500 |

| 4 | Trask River Route | From Patton, it would have roughly followed Patton Valley Road to Cherry Grove, then followed the Tualatin and Trask Rivers to Tillamook; partially followed the old Trask River Wagon Toll Road | $3,098,011 |

| 5 | Vernonia-Saddle Mountain Route | From Vernonia, it would have followed the Vernonia-Hamlet Route to near Grand Rapids, but instead continued west near Saddle Mountain and the Lewis and Clark River to Seaside | $3,542,500 |

| 6 | Salmonberry River Route | From Timber, it would have roughly followed Cochran Road to Cochran, then followed the Salmonberry River west to its confluence with the Nehalem River near Foss Road, then roughly followed Foss Road to Mohler | (not estimated) |

Also included in the report were proposals for several connecting links between the above routings and Portland which would bypass cities like Hillsboro, Beaverton and Forest Grove to allow drivers to travel at higher speeds[30]. A few of them were eventually constructed with some modifications, including OR-47 from Banks to Vernonia (opened c. 1936), US-26 from Manning to Portland (opened 1948), and the southern Forest Grove Bypass (opened 1974).

Of the original six routes investigated, the state highway engineers found that the Ridge Route, Wilson River Route and Vernonia-Hamlet Route best met the OSHD's engineering requirements[30]. Each route's western terminus targeted a different part of the northern coast: The Vernonia-Hamlet Route for Clatsop County resorts, the Ridge Route for northern Tillamook County lumber and fishing interests, and the Wilson River Route for central Tillamook County farms — all deemed feasible termini for a highway in the report[31]. While the engineers preferred the Ridge Route over the other two, it had some disadvantages. It was the longest of the three, and it passed along the ridgeline at a height of 3,200 feet, about 1,500 feet higher than the other two; this would increase potential maintenance costs for inclement weather and the length of time the road would be affected by such conditions[30].

Not long after the report was submitted to State Highway Engineer Klein, people and organizations throughout northwest Oregon began competing to have the highway pass through or terminate in their town:

- The Garibaldi Lions Club and Nehalem Bay Chamber of Commerce supported the Ridge Route[32], as did citizens of Cannon Beach[33] and Rockaway[34].

- The newly formed Tillamook County Chamber of Commerce supported both the Ridge and Wilson River Routes[35].

- The citizens of Tillamook themselves supported the Wilson River Route[36].

- The Vernonia Chamber of Commerce supported the Vernonia-Hamlet Route[37], as did citizens of Seaside[34].

On the legislative front, State Representative George P. Winslow of Tillamook submitted a bill directing the OSHC to plan and construct a short highway to the sea along both the Ridge Route and the Wilson River Route[38]. This effectively would have given Tillamook County a total of three major highways for beach-bound traffic from the Willamette Valley, versus one for Clatsop County; however, Cannon Beach residents preferred this route to the Vernonia-Hamlet route, where they would be "left on a side road, as usual"[34].

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wayne, Tyler. "Great Plank Road," Oregon Encyclopedia, last updated 29 August 2019, last accessed 27 February 2021

- ↑ The Sunday Oregonian. "The Immigration of 1844," 13 July 1884, p. 1

- ↑ City of Beaverton. "History," last accessed 27 February 2021

- ↑ Tims, Dana. "Beaverton Road Project Unearths Oregon History," OregonLive, 21 August 2015, last accessed 27 February 2021

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Plank Roads," 27 February 1872, p. 1

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Washington Co. Plank Road," 1 April 1872, p. 3

- ↑ Journal of the House of the Legislative Assembly of the State of Oregon, 1885, p. 144

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "The Legislature," 29 January 1885, pp. 2 & 4

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Roadbook of Oregon," 11 February 1897, p. 8

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Oregon State Highway Commission minutes, 21 March 1921, pp. 908-909

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Roads Lead From As Well As To," 14 October 1931, p. 8

- ↑ Oregon State Highway Commission minutes, 16 January 1931, p. 2886

- ↑ Oregon State Highway Commission minutes, 18 May 1937, pp. 7354-7355

- ↑ Multnomah County. "Canyon Road (SW) construction, 1926-1930," last accessed 28 February 2021

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 Miller, Edward M., The Sunday Oregonian. "Visitors Are Amazed and Delighted by Oregon Highways", 28 December 1930, p. 4

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 16.6 Wayne, Tyler. "Great Plank Road," Oregon Encyclopedia, last updated 29 August 2019, last accessed 27 February 2021

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Prosch, Thomas W. "Notes from a Government Document on Oregon Conditions in the Fifties," Oregon Historical Quarterly, Vol. VIII, Willis S. Duniway (Salem, OR), 1907, p. 195

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Langille, W. A. "Saddle Mountain State Park", Oregon State Parks Department, 28 Aug 1947, pp. 3-4

- ↑ Oregon State Highway Commission minutes, 27 November 1917, p. 337

- ↑ General Laws of Oregon, 1919, Chapter 345

- ↑ General Laws of Oregon, 1931, Chapter 90

- ↑ Weingroff, Richard F. "From Names to Numbers: The Origins of the US Numbered Highway System," Highway History, Federal Highway Administration, last updated 27 June 2017, last accessed 28 February 2021

- ↑ City of Gearhart. "History", last accessed 12 March 2021

- ↑ The Pacific Northwest Chapter, National Railway Historical Society. "Astoria And Columbia River Railroad: History", 2009, last accessed 12 March 2021

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Seaside Is Festive in Honor of Road," 30 June 1916, p. 9

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Road to Astoria Is Fair," 23 July 1916, p. 8

- ↑ Blakely, Joe R. Building Oregon's Coast Highway 1936-1966: Straightening Curves and Uncorking Bottlenecks, 2014, pp. 17-18

- ↑ Oregon State Highway Commission minutes, 28 August 1930, p. 2790

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 The Morning Oregonian. "Lakeview-Burns Highway Assured," 17 January 1931, pp. 1-2

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 30.4 Miller, Edward M. "Highway Engineers Find Three Routes to Coast Feasible," The Sunday Oregonian, 25 January 1931, p. 4

- ↑ Miller, Edward M. "Ridge Route Road to Ocean Backed," The Morning Oregonian, 20 January 1931, pp. 1 & 6

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Ridge Route Indorsed," 26 January 1931, p. 6

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Up to Commission to Act," 21 August 1931, p. 10

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 The Morning Oregonian. "Cannon Beach Wants Ridge Road," 21 August 1931, p. 10

- ↑ The Sunday Oregonian. "Chamber to Be Formed," 25 January 1931, p. 14

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Those Who Come and Go," 27 March 1931, p. 8

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Those Who Come and Go," 28 August 1931, p. 11

- ↑ The Morning Oregonian. "Double-Route Bill Ready to Present," 21 January 1931, p. 17